The hippie movement was alive and well in 1970, riding on the waves of the 1967 Summer of Love where more than a hundred thousand hippies converged on San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district to celebrate counterculture music, drugs, free love, and anti-war sentiment. In 1969, Woodstock, New York became famous for its three days of peace and music.

Nine months later, hippies would once again amass—this time at a setting much closer to home. This local music event would go down in history not just for the calibre of bands scheduled to play but the memorable events that followed.

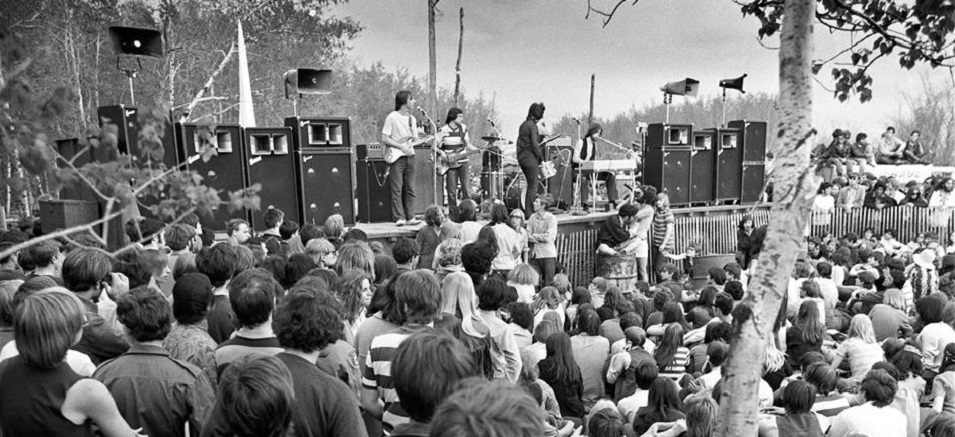

Sunday, May 24, 1970 was the day of the Niverville Pop Festival.

Niverville’s Woodstock

During the 1960s and 70s, Winnipeg was a hotbed of young musical talent. One of those bands, called Brother, was quickly rising in notoriety. Its members included Bill Wallace, Kurt Winter, and Vance Masters, and their talent established them as one of the city’s hottest supergroups.

Harold Wiebe, formerly of the Niverville area, recalls a night spent in the pub of the Westminster Hotel. There, friend and band member Bill Wallace joined him for a drink between sets. Wallace shared with him an idea to recreate Woodstock right here at home.

But unlike Woodstock, Wallace wanted this event to have a charitable purpose. Wiebe was aware of just the cause: the Lynne Derksen Oxygenator Fund.

Just one year earlier, teenager Lynne Derksen had fallen from a hayride, resulting in life-threatening injuries. Her medical treatment depended on the use of an oxygenator, a device which acted like an artificial lung.

Unfortunately, Derksen didn’t survive her injuries, but the students and staff of the Canadian Mennonite Bible College established the fund in her memory. Their hope was to raise $30,000 to present to the Winnipeg General Hospital for the purchase of an oxygenator.

Wallace and Winter wasted no time in using their influence to pull together local deejays and musicians willing to support the cause. Wiebe became frontman for the logistical planning.

As for a location, Wiebe’s parents owned an acreage southeast of Niverville, the idyllic spot for a rock festival.

“Of course, we were thinking that this was going to be a small thing, but as the advertisements started coming out on the radio we realized the interest that was developing… and we knew we needed a different venue for it,” Wiebe says. “You couldn’t turn on a radio station, certainly not the ones us young people listened to, without hearing something about the Niverville Pop Festival coming up.”

Wiebe approached his farming neighbour, Joe Chipilski, for the use of an abandoned homestead just one mile away. With almost 60 acres of land, and much of it grassy, the band agreed to the change of location.

Parking was also covered. Another farmer agreed to let the festival use the quarter section of dirt field immediately across the road from the Chipilski land.

In the spirit of hippie culture, others, too, began offering their goods and talents for free. Wm. Dyck and Sons of Niverville provided a 34-foot flatbed trailer for use as a stage. Garnet Amplifiers of Winnipeg, a longtime proponent of up-and-coming talent, generously supplied the entire sound system.

One of the only expenses incurred was $34 to run in some temporary electricity.

In no time, 15 bands were booked to hit the stage, including Brother, making their last public appearance as a band before guitarist Kurt Winter left to join the Guess Who, replacing Randy Bachman.

Hosts of the event included rock radio deejays from CFRW (now known as TSN 1290). The ticket price to attend was set at one dollar.

Meanwhile, in the nearby village of Niverville, some parents and church leaders were growing concerned over rumours of the Woodstock-like festival. Resident Steve Neufeld, just nine years old at the time, recalls hearing of special prayer meetings likely dedicated to the safety of the community’s young people, who were at risk of exposure to the sex, drugs and rock-and-roll lifestyle such events were known for.

Rumour has it that the RCMP, too, went door-to-door warning residents to stay inside and lock their doors on May 24.

Unlike Woodstock, which required a change of locations not once but twice due to public outcry, the Niverville Pop Festival went ahead undeterred.

A Surprising Turnout

The first band was scheduled to play at 3:00 p.m., and organizers were prepared for about 5,000 attendees. Earlier that afternoon, however, young people began pouring in, arriving on Winnipeg transit buses and cars from all over the province.

Before long, traffic was backed up along Highway 59 as well as along all the approaching side roads.

“I don’t think any of us really anticipated the magnitude of this thing and the number of people that would be there,” says Gary Stott, friend of Wiebe and event assistant. “It seems to me back then the reports were that there was a lineup on the 59 Highway [all the way from Winnipeg].”

Traffic slowed to a crawl as the access roads to the venue became clogged. Anxious drivers began abandoning their cars anywhere they could find space, including in the ditches all around the venue and along both sides of the highway as far as the eye could see. Attendees trekked in for miles on foot.

For Wiebe, collecting admission became an exercise in futility.

“We saw the masses coming across the fields,” Wiebe says. “Every direction you looked for 360 degrees was people walking. In short order, I had to dispatch possibly a half-dozen or more of my friends with carpenter’s aprons and some change… in as many directions as feasible to try and collect.”

Storing the collected funds also required some creativity. Wiebe recalls taking a hatchet to the trunk of a car and creating a slot into which money could be dropped and safely stashed.

The Bands

Joey Gregorash of the band Walrus got the crowd warmed up with the famous Woodstock fish cheer. Echoing his chant were the voices of more than 10,000 attendees and counting.

On stage, Brother performed their set, which included a few songs that would later be made famous by the Guess Who: “Hand Me Down World” and “Bus Rider.”

Wiebe says bands began showing up that hadn’t been on the roster, hoping to get their time on the stage.

“Burton Cummings wasn’t on the [playbill], but he just showed up and [played],” Wiebe says. “The Guess Who was already a big deal by then. They had [hits like] ‘American Woman’ and ‘These Eyes,’ which had been on the radio already for quite some time… He saw the weather coming and he wanted to make sure that he got on stage.”

“My girlfriend and I were very cool, or so we thought,” muses Linda Roy, then a 16-year-old Landmark Collegiate student. “But arriving at the festival was a bit much. I remember feeling like we were out of our league. I’ll never forget one gal was wearing a black kind of fishnet-type tanktop—see-through, and no bra. That was a bit wild for me. Something we didn’t see in Landmark Collegiate.”

Former Niverville resident Bob Wallace remembers attending the festival as a 20-year-old.

“When I arrived, the bands were playing on the stage… and there were several food and beverage kiosks set up, and the smell of pot was fairly obvious,” Wallace says. “People were setting up for an afternoon of eating and drinking, smoking and generally having a good time. The mood was upbeat and controlled.”

Both Stott and Wiebe conclude that, had the festival been able to carry on without interruption, it would have continued through the night and well into the next day.

The Deluge

By around 5:30, as blues rockers Chopping Block were taking the stage, clouds moved in over the sun. As if the gods of Woodstock had been summoned, a light sprinkle of rain began to fall.

And it soon turned into a torrential downpour.

“It started to spit and some people had plastic tarps and things to cover themselves, but it just kept getting heavier and had some hail thrown in,” Wallace says. “When it really opened up, people started heading for the cars to wait it out, but it didn’t let up.”

“I remember everyone really having a lot of fun before the rain,” guitarist Ron Siwicki later told rock historian John Einarson for an article in the Winnipeg Free Press. “And even when everyone was sitting in their cars in the rain, they were still partying and having fun. It was pretty bizarre, like the spirit of Woodstock transported to Manitoba.”

Darl Friesen attended the event as a 14-year old, along with an older chaperone.

“Looking for a quick way out of the rain and out of the festival, I squished into Clifford Kemila’s VW bug with an incredible amount of other people,” Friesen recalls. “It was like a clown car.”

It soon became evident that the rain wasn’t about to let up, and in short order the grounds transformed into a thick, sloppy muck. Trying to access vehicles in the dirt parking lot was like slogging through quicksand.

Neufeld remembers being in the backseat of his parents’ car, driving past the chaotic scene in the downpour.

“There were cars in the ditch that had water up to their windshield,” Neufeld says. “As a young kid, I’d never seen anything like that before.”

“Everyone was up to their kazoos in mud,” Stott adds. “They would slide down [the ditches] on the Tourond clay into the mud and just enjoy the time.”

As music fest turned to mud fest, everyone got to work helping people extricate vehicles from the sticky Red River gumbo. While some could be pushed to higher ground, others were impossible to budge. Many people who’d come in shoes left barefoot, their footwear lost deep in the mire.

Forty-five years later, soles of shoes were still being unearthed in the area.

“There were people in the ditch and there was a metro transit bus that got stuck on the dirt road,” Wallace recalls. “I remember it being absolutely useless in the mud and a group of people spun it around 180 degrees so it was headed back towards the highway and someone showed up with a tractor to tow it back to the 59.”

Audio engineer Michael Gillespie told Einarson, “I had parked my CKY-marked Montego station wagon in a field and got out onto a road only to slide sideways and tip into a ditch. The car was on its side. About 20 people lifted the car out of the ditch back onto the road.”

Many others simply abandoned their vehicles and headed out on foot. Muddy and rain-soaked, they decided to thumb a ride home.

The cars parked on high ground along the highway became taxicabs for the stranded.

“Each one was loaded down with people on the roof, on the hood, in the back of truck boxes, wherever they could hang on and catch a ride, myself included,” Wallace said. “I rode on a hood all the way to Niverville.”

The Locals Step Up to Help

In no time, neighbouring farmers showed up on their tractors, pulling vehicles through the mess. Some locals remember the farm truck sent by Mr. William Dyck to carry stranded young people back to his home in Niverville.

“Motivated by his care for his fellow human beings, his faith took him there to bring people back to his home and clean them up, feed them, and give them rides to Winnipeg,” Neufeld says. “That really struck a cord with me.”

Luckily for Linda Roy and her friend, they left before the rain began.

“I ended up going to Niverville with my brother-in-law Ben and I worked till 1:00 a.m. at Snoopy’s,” Roy says. “We sold every hotdog and hamburger in the joint. Lots of muddy stragglers stopped in all evening.”

Snoopy’s was a small hamburger stand situated on Niverville’s Main Street. Owner Susan Friesen told Einarson of her experience on the evening of the festival.

“After the rain, we started getting people coming to Snoopy’s,” Friesen said. “They were all tired, wet, cold, and hungry. We ran out of everything and borrowed supplies from another restaurant in town called The Pines. We used up all of their fast food supplies, then called the local grocery store to get more. They were nice enough to open for us. We fed a couple hundred people. We stayed open later than usual, until we ran out of food.”

Niverville’s Claim to Fame

The next day, the Niverville Pop Festival headlined the front page of both Winnipeg newspapers.

According to Einarson, “It was even the subject of discussion at the provincial legislature when NDP MLA Russ Doern, who claimed to have been at the festival the day before, announced, ‘There was a sizeable crowd of young people there who… participated in the best manner. They were well behaved, they thoroughly enjoyed themselves, and I think they made this a great success.’ He went on to laud the charitable goal of the event and praised townspeople and local farmers for pitching in when the rain hit. Premier Ed Schreyer suggested that perhaps the festival ought to be called the Tractor Rock Festival.”

“Without the rain, I think this pop festival would have been a huge success,” Wallace says. “I just think the rain was not anticipated and the number of people already there and on their way there when it was rained out would have totalled at least upwards of 50,000 to 100,000 strong.”

The Donation

Somewhere in the area of $10,000 was collected that day and delivered to the supporters of the Lynne Derksen Oxygenator Fund. Gary Stott recalls some hesitation on behalf of the Canadian Mennonite Bible College on accepting donations derived from such a source. In the end, though, they conceded.

The festival planners never heard about the money again or whether the goal of the fund was ever achieved.

That is, until January 2014.

According to the website of Brother band member Vance Masters, curiosity led Masters’ wife Bev and others to research the outcome of the fund. They discovered an inference to it in a scanned document taken from a March 1973 issue of The Mennonite Mirror.

“We contacted the Health Sciences Centre in Winnipeg to inquire if they had any information regarding the Lynne Derksen Oxygenator Fund,” says Bev Masters. “With so many years having passed and knowing that record-keeping back in those days was nowhere near as stringent as today, we were not optimistic that we would even hear back from the facility.”

Within 24 hours, however, a director at HSC responded that they’d solicited the help of the hospital archivist. Within two days they had answers.

According to the report, “in February 1981, the Board of Trustees… of the Canadian Mennonite Bible College agreed that the fund be used for the purpose of providing specialized training for personnel in the intensive care field at the Health Sciences Centre… As of last year, this fund was amalgamated into an endowment fund with other trust accounts to create a fund for the education of nurses. The new fund will continue to have the Lynne Derksen Award for a staff person obtaining specialized training in the field of intensive care.”

Thanks to the organizers of the Niverville Pop Festival and others who donated to the cause, Lynne Derksen’s legacy continues to live on 50 years later and will keep going into the unforeseeable future.