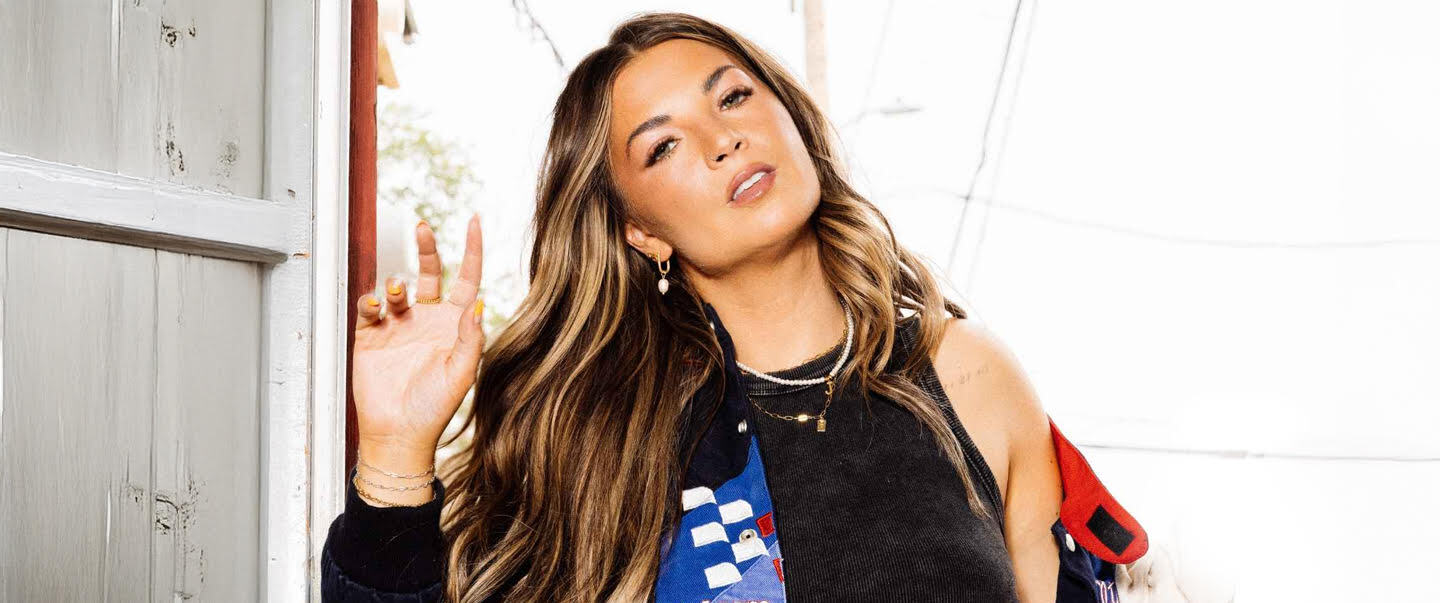

K.R. Byggdin may not technically be Mennonite, but you’d never know after reading their book, Wonder World.

Byggdin grew up in Niverville and still seems to have their finger on the pulse of the small, predominantly Mennonite towns that dot our province. They say they are “Mennonite by osmosis.”

In the acknowledgements of Wonder World, Byggdin calls the book “a complicated, queer love story to the prairies.” And that is indeed how it reads. The main character, Isaac, grew up on the prairies but then moved to the east coast. A death in the family sees him return to his small Manitoba town and brings back all the joys and complications of life there.

Isaac and his pastor father are estranged due, in large part, to Isaac’s sexual orientation. His grandfather, one of the only family members who Isaac believed actually cared for him, has passed away.

There are some similarities between Isaac and Byggdin’s journeys. After graduating from Niverville Collegiate Institute, Byggdin attended university and met their future spouse, who was from the east coast. The two married and made their home in Halifax.

Once in Halifax, Byggdin says they began to conceptualize the novel.

“I had all these little moments of realizing that I’m still in Canada but I’m in a very different region and culture,” says Byggdin. “That made me kind of reflect on my childhood here in Manitoba—the things that were difficult, the things that I really loved, some of the foods I really miss.”

Byggdin started writing the novel in 2018. Reflecting on their time in the prairies, they realized that processing that time of life could be done in an artistic way. Soon the novel began to take shape.

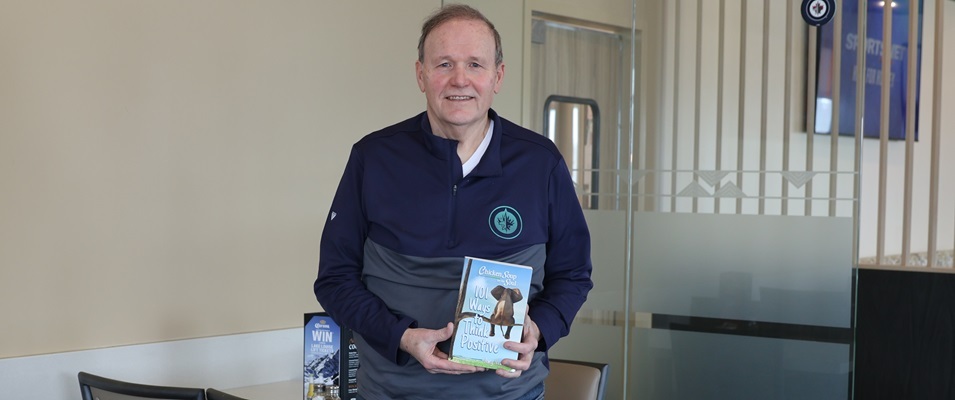

In 2011, Byggdin was working a summer position in Niverville as the town’s youth job coordinator. That position was based out of the town’s administration office. They recall that one day Mayor Greg Fehr came into the office and handed Byggdin a book he thought Byggdin would enjoy. That book was A Complicated Kindness by Miriam Toews.

“My first thought was, ‘Good Christians don’t read Miriam Toews,’” recalls Byggdin. “Because that’s what I’d heard! But at the same time I thought, ‘I really like Greg and Greg is saying to give it a try, so I might as well.’”

Reading that book was thrilling for Byggdin.

“It was the first time that I could say that I understood these streets or this culture. The first time that I could understand so intimately what someone was writing about. That was the first time it hit me that books don’t have to be set in London or New York or Paris. Books can also be set in places like southeastern Manitoba.”

Byggdin says that one of the things they appreciated most about Mennonite culture is the closeness of families and communities.

“There is a powerful sense of belonging and inclusion that can come from that,” they say, adding that they appreciate the food of the Mennonites. “Platz, vareniki, farmer sausage… I had to learn to make my own cottage cheese vareniki in Halifax!”

However, growing up in this place also came with challenges when it came to accepting an important of themselves.

“The difficult thing, though,” they say, “is that growing up in a religious context, I didn’t always feel as though I could express or even just internally accept myself as a queer, non-binary person. I felt like those two things had to be at odds. With writing this book, I wanted to challenge the idea that you cannot be queer and Mennonite or that you cannot be queer and rural Manitoban.”

Byggdin says there have always been LGBTQ2S people in our small towns. It’s just that we haven’t traditionally talked about them. They say they are hoping to keep the conversation around this topic open.

“These identities are not at odds with one another but can actually coexist and make a community stronger by embracing that diversity,” Byggdin says.

That diversity doesn’t just apply to LGBTQ2S people, either. Byggdin suggests that the same idea applies to neurodivergent people or immigrants or various other groups. All these people are here. We just need to acknowledge them and their contributions to our society.

“Southeastern Manitoba belongs to everyone,” they say. “I wanted to write a story that provides a pathway of a hopeful future. A narrative of hope.”