It’s been exactly 150 years since the first wave of Mennonites arrived in Manitoba back in 1874. Over the course of the next few years, around 7,000 of these people of faith left imperial Russia on the promise of religious freedom and military exemption overseas.

To commemorate this milestone year, a new 70-minute docudrama, Where the Cottonwoods Grow, is being released for early screenings. From independent filmmaker Dale Hildebrand, the film chronicles the hardships and struggles faced by the Mennonites as they started their lives anew in a foreign land.

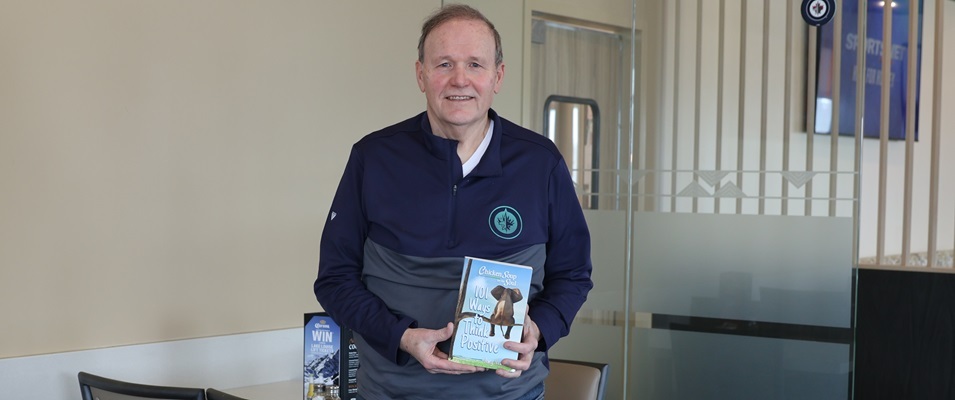

Hildebrand grew up Mennonite in southern Manitoba, in communities like Halbstadt and Edenburg near the U.S. border. Today he lives in Toronto and works as a producer, director, writer, and cinematographer. He has been the recipient of more than 50 awards and nominations.

He’s also shot films far afield, in places like the war zones of Afghanistan, the peaks of the Himalayas, and the plains of Africa. But Where the Cottonwoods Grow brought him back to his rural roots.

The opening scene is shot in Neubergthal, Manitoba.

“We start the film with a woman walking across the cold, barren, frozen land of Manitoba in 1924,” says Hildebrand. “She’s carrying a book and walking past these cottonwoods and arriving at a house barn. There’s a gathering of women who are there for a day of quilting.”

The woman sits down with her peers and proceeds to read from the book, regaling the women with stories drawn from journals and letters written by their ancestors 50 years earlier. This scene lays the foundation for the balance of the film.

“Each quilt patch is another chapter of the story,” he says. “And so by the end of the film, the story has been told and the quilt has been made.”

As for the title, Hildebrand says he drew inspiration from the cottonwood trees that surrounded his property when he was a child.

Despite his roots, Hildebrand admits to learning much about his ancestral background in the year and a half it took to produce the film. Some of his best sources were local historians well-versed in Mennonite history. A few of them appear in the film, much of which was shot at the Mennonite Heritage Museum in Steinbach.

It was here, as well, where the film’s musical score found inspiration.

“We recorded actual väa senja (before singers) in Steinbach in one of the old churches in the museum,” says Hildebrand. “We also recorded some choir singers in the Sommerfelder church, and then we scored it with many different elements, like a string section and all of that. It sounds stunning.”

But not every scene could be shot on location. Take, for example, the seven-week journey by ship across the Atlantic. These sequences have been realized through computer-generated imaging (CGI).

In an effort to maintain historical accuracy, Hildebrand says he visited a shipyard in England where he was able to obtain the original blueprints for the sister ship to the one the Mennonites in his film would have travelled on.

The film seeks to be honest in its telling of this arduous journey. Many of those aboard the ship died en route.

“The Mennonites that were in Russia were very secluded,” he explains. “Most of them had never before seen a train or a ship, never mind travelling 20,000 kilometres on one.”

Landing on Canadian soil also exposed them to sicknesses to which they’d built no immunity. For this reason, many Mennonite immigrants didn’t make it through their first year in Manitoba.

But their arrival wasn’t all clouded with hardship. Thanks to help from the Indigenous and Métis peoples, the new arrivals were quickly taught the skills and practicality of sod houses, as well as the use of native herbs for medicines and balms.

Hildebrand doesn’t gloss over the historical reality that the arrival of European immigrants such as the Mennonites brought colonialism along with it, displacing many Indigenous and Métis from their ancestral lands.

Instead he has weaved their stories right into the film’s fabric by including interviews with the great-great-grandnephew of Louis Riel, as well as Chief Yellowquill, the descendent of a chief signatory to Treaty 1.

“We filmed them at the place where Treaty 1 was signed in Lower Fort Garry… We went to the source for so many of these scenes and they just took on a life of their own.”

For the scripted portions of the film, Hildebrand had a unique partner: his sister Eleanor Chornoboy. Chornoboy is the author of several Mennonite books, as well as an actor. In the film, she takes on the role of the story reader at the quilting table.

The idea of casting the story from the viewpoint of women, Hildebrand says, was no accident.

“Most of the journals in the time [of the migration] were written by men or boys,” he says. “There weren’t many written by women. After the movie Women Talking, I didn’t want to turn this film into ‘men man-splaining,’ so that’s why I brought in all of these women, quilting, and storytelling. It’s almost the women that are carrying forward the history.”

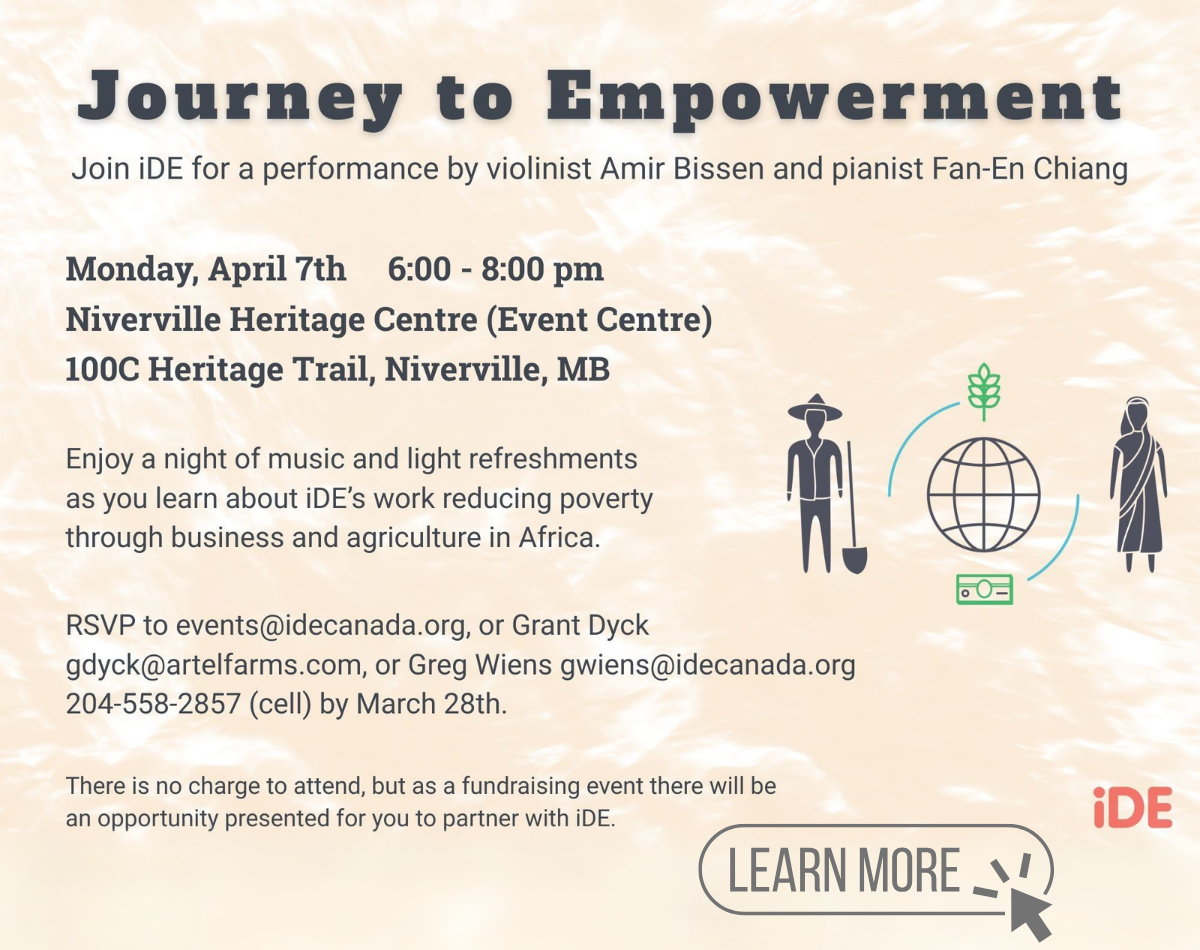

As a Canadian filmmaker, Hildebrand is aware of Manitoba’s bid to become a film production hub. He’s also very familiar with the state-of-the-art production technology which will soon come to Jette Studios in Niverville, where a 270-degree LED screen, colloquially known as “The Volume,” is set to go up next year. There are only a handful of such studios in North America today.

“The Directors Guild of Canada chose eight directors to be the first to shoot with The Volume here in Toronto. I happened to be one of them,” says Hildebrand. “I did a whole castle rampart thing on The Volume and it was just phenomenal shooting.”

Manitoba will host four early screenings of Where the Cottonwoods Grow, including at the Steinbach Christian Mennonite Conference Church on December 1, the P.W. Enns Centennial Concert Hall in Winkler on December 4, the First Mennonite Church on Notre Dame Avenue in Winnipeg on December 15, and the Buhler Hall in Gretna on December 19.

In the new year, Hildebrand hopes to pitch the film to buyers for further digital distribution.