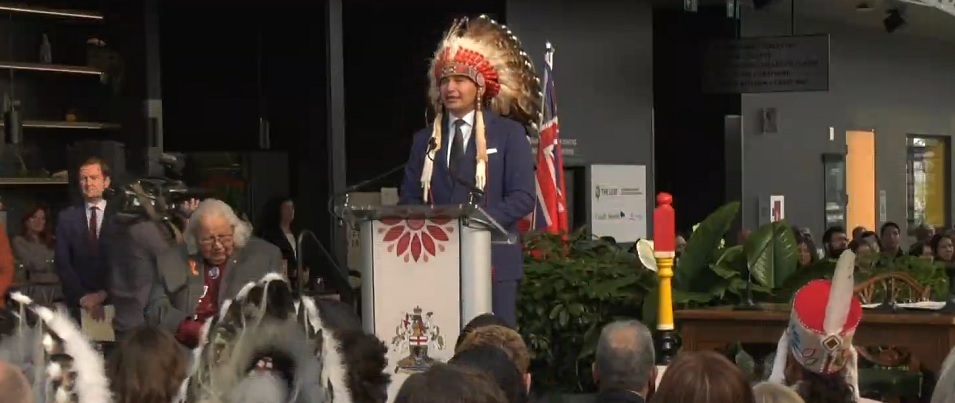

Today, Manitoba swears in its first First Nations premier, Wab Kinew. This watershed moment is significant not only for the almost 165,000 Indigenous people who make Manitoba home, representing 12 percent of the population, but for the province as a whole.

Kinew hails from the Onigaming First Nation of Ontario, which is part of Treaty 3 territory spanning parts of northwestern Ontario and southeastern Manitoba. Exactly 150 years prior to Kinew’s election win, to the day, Treaty 3 was signed by his people. That official signing took place on October 3, 1873.

Even so, Kinew says that the NDP campaign was all-inclusive, focusing on the things that matter to all Manitobans such as healthcare and making life more affordable.

“I didn’t run on being the first First Nations premier,” Kinew said in a post-election press release. “I put my name on the ballot to try and be the best premier.”

Second Chances

Kinew’s historic election win is also a story of second chances. Indeed, he referenced it in his victory speech on October 3.

“I was given a second chance in life, and I’d like to think that I’ve made good on that opportunity,” he said.

One may assume he was, at least in part, referencing a period in his young adulthood when he faced convictions of assault and impaired driving, which were later pardoned.

These were low points in Kinew’s life. Despite this aspect of his past being repeatedly brought up on the campaign trail, he says that he reconciled himself with it back in 2015 when he went public in his memoir, The Reason You Walk.

It was around 2005, immediately following his criminal convictions, when Kinew first began believing in second chances. He’d read a story in the Winnipeg Free Press about a Canadian Olympian who’d been chosen in spite of the athlete’s past criminal record.

It sparked a letter from Kinew to the Free Press, asking when it is that a person with a record gets a second chance.

This heartfelt query piqued the interest of the CBC, who later took Kinew on as a reporter and host for both local and national radio and television shows.

Come the 2023 election, Lloyd Axworthy, an elder statesman and former Minister of Foreign Affairs, threw his support behind Kinew, framing him as a man of integrity and character deserving of second chances.

Axworthy, who also served as president of the University of Winnipeg, was aware of Kinew’s role as Director of Indigenous Inclusion at the university. Kinew had been instrumental in raising money to implement programs and create scholarship funds for inner city students.

“His past was what motivated him, because he wanted to see that that path would be a driver for what he could do in the future,” Axworthy said in a press release.

And from behind the podium on victory day, the premier-designate also extended an offer of second chances to the young Indigenous voters who were listening.

“I want to speak to the young neechies out there,” he said, using a term that translates to friends. “I was given a second chance in life… and you can do the same.”

He encouraged these youth to pursue a better life while pledging to come alongside them by providing addictions recovery assistance, job training, and healthcare solutions close to home.

Proud of First Nations Heritage

Wabanakwut Kinew spent his childhood years in Kenora before his family moved to Winnipeg.

His father, Tobasonakwut Kinew, is a well-known Anishinaabe leader and traditional knowledge keeper while his mother, Kathi Kinew, worked in the department of Indigenous Studies at the University of Manitoba.

With such a strong connection to his heritage, it seemed natural that Kinew, too, should seek to understand the traditional ways of his people. Over the years, Kinew has practiced the traditional Sundance and Midéwiwin ceremonies. He’s also a pipe carrier, drummer, and traditional singer. He continued in these traditions to become a powwow dancer, sewing his own ceremonial regalia.

His first name, Wabanakwut, translates to “early morning grey cloud” in the Anishinaabe language.

But this is not a reference to the melancholy grey one may imagine. Instead it signifies the colour of hair as people age. Thus, it carries a message of wisdom, dignity, and honour.

His ancestral name carries equal symbolic weight. The name Kinew references the golden eagle—a solitary, powerful creature revered by the Indigenous peoples. Golden eagles are believed to be teachers of leadership, which is signified by the eagle feathers worn in Anishinaabe headdresses and hair.

Indeed, Kinew wore just such a headdress while presiding over his and his new cabinet’s swearing-in ceremony on October 18.

“Wearing an eagle feather means trying to see as eagles do; from the highest vantage, viewing a territory without divisions such as race, gender and class and trying to envision a place where humans, animals, birds, fish, earth, water and sky can all work together,” wrote Niigaan Sinclair in a recent Winnipeg Free Press article.

As is also common in Anishinaabe tradition, Kinew’s clan is connected to the lynx, the spiritual animal from which they learn.

“Lynx clan members among Anishinaabe carry a very important and sacred duty: to protect our nation,” added Sinclair. “They are warriors, leaders, and spokespeople.”

Traditionally, members of the lynx clan would be the first to be sent into new territories and build relationships with the aim of making treaties.

Without question, Kinew has big shoes to fill, both in his naming and new role as Manitoba’s next premier. And on the day following his election, Kinew told Manitobans that he intends to do it with the grace and honour bestowed on him by his ancestral people.

“If there are expectations that people have of us, and of myself as a leader, I would say that I’m going to meet them with the same approach of reverence and humility that I will bring to every task as the next premier of our province.”