The bucket list—a phrase coined to encompass all the things a person would like to do before they “kick the bucket.” Most of us have a list like this, which might include big life accomplishments or smaller, more attainable dreams.

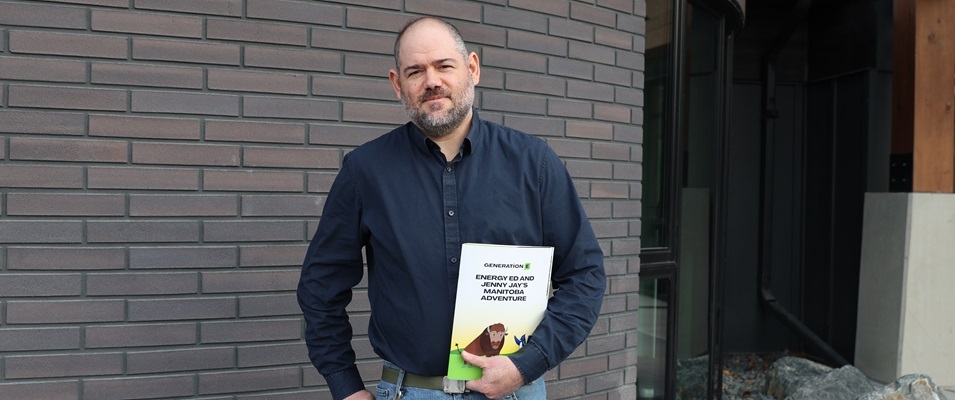

Niverville resident Brian Hildebrand has been checking a big life accomplishment off his bucket list this summer. In July, after five years of planning and dreaming, he walked 800 kilometres along the Camino de Santiago in Spain.

The Camino de Santiago directly translates as “the Way of Saint James” and encompasses many different routes from a variety of European countries, all ending at the shrine of Saint James in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, in Galicia in northwestern Spain. It’s believed by many that the remains of Saint James are buried here. From as far back as the ninth century, pilgrims have walked the camino as a spiritual journey.

Today, the camino is the most popular Christian pilgrimage route in the world and is recognized by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) as a World Heritage Site. More than 1,800 monuments and historic buildings line its path.

Though it had its beginnings as a spiritual trek, hundreds of thousands of visitors from around the world walk the camino for different reasons. For Hildebrand, it was an opportunity to challenge his body and mind while seeing a part of Europe in a way most people never would—by foot.

Hildebrand first heard of the camino while watching the movie The Way, starring Martin Sheen. The movie tells the story of a father, estranged from his son, who travels to Spain to collect his son’s cremated remains after the young man’s trek ends in tragedy. Sheen’s character makes a life-changing decision to complete the journey for his son, spreading his ashes at significant spots en route to Galicia.

“Ever since [seeing the movie] I thought, ‘Man, I have to do that one day,’” says Hildebrand. “And then it just slowly grew in me. It’s a movie of pain, finding joy, redemption, and I was just captured by the story. I got caught up in the walking part, walking day after day, having the same routine, having a goal and achieving it. And having all of that time just to think. I probably read about a dozen books plus watched hours and hours of YouTube [videos about the] Camino.”

Encouraged by his wife Joyce and four children, he set out for Spain for five and a half weeks with just a backpack and a dream.

Hildebrand’s journey began in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port in southern France, a popular location to begin the 800-kilometre trek. Here he received his credencial, or pilgrim’s passport, which allows pilgrims access to inexpensive accommodations along the way. At each stop the passport is stamped, providing a record for the traveller and serving as proof at the Pilgrim’s Office in Santiago. Upon presentation of the passport at the end of the journey, pilgrims receive a compostela, a certificate of completion.

Following a pilgrim’s guidebook, Hildebrand mapped out his journey, which would cover the extensive route in 33 days if all went well. The plan was to awaken before dawn each morning, walk 24 to 30 kilometres (depending on the route) and arrive at an albergue (a hostel) by noon and before the midday heat.

“I brought music, but I liked the silence of it,” says Hildebrand. “I often started when it was still dark, as early as five in the morning. You wouldn’t really see much light in the sky till 6:30 or 7:00 so a lot of it was walking with my headlamp. When you can’t see anything, your sense of hearing increases and you notice a lot of different things.

“I might have missed some views, but I didn’t miss the sounds of the day waking up. Some of the forests I walked through I experienced in a different way. The trees would come into view and the bugs would be drawn to the light of the headlamp and bats would be swooping in to eat them.”

Temperatures sometimes soared in the afternoons to 38 degrees Celsius. Arriving early to his albergue not only meant avoiding the heat, but having first option to the choicest beds, a shower, and a rest before exploring the township. As other international trekkers trickled in, they would often gather around long tables, sharing stories and good food.

Personal injuries, of course, were among those stories. Blisters, tendonitis, and pulled muscles were common threads.

“I had worked into my plan three extra days in case I did get injured, but I didn’t need to. I was tempted to [take a rest day] many times, but if I would have stopped I would have been behind the people that I [met up with at the end of each day]. Sometimes it was just mind over matter and pushing on.”

By day two, he was suffering with massive blisters on the balls of his feet. A kindly albergue owner applied dressings to his feet and instructed him in footcare and proper shoe lacing. The key, he discovered, was applying feminine hygiene napkins to the insoles of his shoes to absorb the sweat, the most common cause of blisters. These became a staple in his backpack.

Rather than journaling his adventure, Hildebrand took daily pictures and videos, sending them home to family and friends who followed his journey as if it was their own. He regularly texted his wife on his long walks, staying in touch as best he could.

“There was several points along the way that I just wanted to quit,” he says. “Why am I doing this? It’s stupid, it’s selfish.”

Hildebrand’s goal was not completely selfish, though. A Grade 4 teacher by trade in Kleefeld, he involved his students in a tangible way. Using a soapstone from a carving class he’d taught, Hildebrand introduced his students to his plan to drop the stone off at a landmark along his trek, the Cruz de Ferro. At this iron cross, the highest point along the camino, pilgrims drop a stone, attaching to it their worries and burdens. Each of Hildebrand’s students was encouraged to rub the stone and leave their worries with it, eventually to be left at the iron cross.

On Hildebrand’s final day, just kilometres from the end, he tripped on an embedded stone, landing hard on his chest. Though the injury wasn’t serious, he entered Santiago that day a champion with bruised ribs and laboured breathing.

“I thought [I] was going to [feel] very euphoric at the end, but [I] wasn’t. I don’t know exactly what I expected, but when I walked into the final cathedral courtyard I thought, ‘Okay, I guess that’s it. I can go home now.’ I was really there to see if I could do it well, and I guess I did.”