This is the second in a series presented by The Citizen which explores the lives of newcomers to our region of southeastern Manitoba. Everywhere we look, new and diverse faces surround us. It’s time to get to know our neighbours and welcome them to our communities.

Massoud Horriat is neither a newcomer to St. Adolphe nor a stranger there. In fact, the name Massoud is as familiar in this small French community as the names of those who have spent their entire lives in the town.

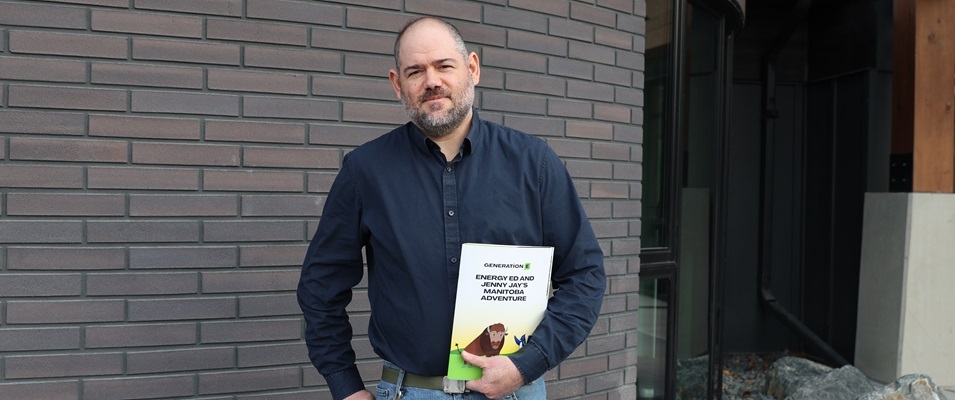

Massoud is the local pharmacist and, while he resides in south Winnipeg, the long hours he spends serving the residents of St. Adolphe from his Main Street business make him feel like one of them.

For more than 30 years, Massoud has called Canada home. For the past nine of those years, Massoud has owned and operated the St. Adolphe Pharmacy, acting as its sole pharmacist.

Massoud is a numbers kind of guy. He remembers dates like they happened yesterday, including the day he first landed in Canada: October 11, 1991.

Born in Iran, Massoud and his family were forced to flee their home country in the late 1980s during the time of the Islamic Revolution. They took refuge in Pakistan until they secured immigration visas for Canada.

While he waited, he took shelter in a city called Lahore.

“I waited there for two years, one day, three hours, and 22 minutes to come to Canada,” Massoud muses.

The Islamic Republic of Iran was born in 1979 and was led by Muslim clerics and the founder of the Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini. What followed in the coming decades, what is still happening to this very day, is a kind of cultural genocide. Iran has been subjected to an oppressive political movement seeking to eliminate any faith group other than Islamic fundamentalism.

Massoud and his family hold to the Baha’i faith, Iran’s largest non-Islamic religious minority. As such, they and thousands of others became targets of the state.

According to Amnesty International, the Baha’i “suffered widespread and systematic violations, including arbitrary detention, torture and other ill treatment, enforced disappearance, forcible closure of businesses, confiscation of property, house demolitions, destruction of cemeteries, and hate speech by officials and state media.”1

Eventually, the Supreme Revolutionary Cultural Council made clear their mandate to ensure that the end of the Baha’i faith in Iran by expelling its adherents from universities and denying them employment or positions of influence.

Based on historical information provided by the Iran Press Watch, tens of thousands of Iranians were found “objectionable” by the state and killed, their bodies dumped into mass graves.

“More than 200 Baha’is were executed during the 1980s and early 1990s and a thousand or more were imprisoned,” states the Iran Press Watch.2

Massoud was in his mid-twenties during those years. He worked as a machinist since the state prevented him from attending university to achieve his dream of obtaining a degree in medicine.

His mother worked as a nurse and his father was an entrepreneur. Tensions for the family grew as they watched people they knew be imprisoned, tortured, or executed for their faith.

“If you are not Muslim, you are not welcome there,” says Massoud.

When Massoud and his family finally decided to flee their homeland, they left homes, property, and vacation villas behind, arriving in Pakistan with little to their name.

Massoud was the first to arrive in Pakistan, Iran’s dominantly Islamic neighbour. Massoud describes it as being only slightly more tolerant of non-Muslims.

Although Iranian refuges weren’t turned away at their borders, they also weren’t allowed to take jobs or pursue an education while holed up in Pakistan, awaiting their uncertain future.

To get by, Massoud learned the Ursu language. His native tongue, Farsi, was not spoken outside of refugee circles.

“You can’t do anything [in Pakistan] and you just barely survive,” Massoud says. “I took a few belongings and some money with me [from Iran] and the United Nations helped us, but very little. You had to make the best of it. It was hard, hard, hard.”

Summers in Pakistan, he says, can get up to 45 Celsius along with high humidity. During his years there, the sewage system in the area in which he lived was deplorable, emptying from local homes right onto the streets and alleyways.

“You had to be careful not to catch any diseases. The hygiene level was [poor].”

Massoud found a small one-room apartment which he shared with about five other bachelors. Later, when Massoud’s parents and extended family escaped to Pakistan, he rented a second room for them.

The bureaucratic process for immigration through the United Nations was anything but easy for the family. Eventually, their moment arrived and they were given the option of immigrating to Canada, America, or Australia. Their chances of gaining visas to a certain country improved if they had family already living there.

“We chose Canada because my sister was here. So I came to Canada and then a month and a half later my parents and my youngest sister came.”

One year prior, Massoud’s sister, her husband, and two children had emigrated to Winnipeg. Massoud took up temporary residence in their small apartment for a few months while he got on his feet.

Soon after, the others came.

“We started from scratch. When we came here, we didn’t have anything. But at least we were free and we were able to get jobs.”

Massoud’s first winter in Winnipeg came as a complete shock to his system.

“I knew it was cold, but hearing about it and experiencing it are two totally different things,” he recalls.

Massoud was 30 when he settled in Winnipeg. Wasting no time, he registered at the University of Winnipeg to fulfill his dream of going into medicine. He took any menial job he was able to find to put himself through school.

“I worked as a dishwasher till 3:00 a.m. and then went to school the next morning.”

But Massoud had no working knowledge of English apart from some superficial language classes for immigrants upon his early arrival. He dug in his heels, undeterred by the many roadblocks that lay in his path, and looked ahead to his certification through the Medical College Admission Exam.

“It was very, very challenging,” he says. “For one example, the physics prof was talking about torque and I thought he was talking about Turkish people and I couldn’t understand the difference. So it was hell, but I did it. I learned English as I studied.”

Thanks to a tenacious spirit, Massoud not only passed his courses but achieved top grades, receiving financial bursaries along the way.

While studying and working, Massoud met up with an Iranian lady friend and recent immigrant to Winnipeg. Soon after, they were married. Not long after that, they were expecting their first child.

The prospect of fatherhood meant Massoud’s plans would change. Two years into his studies, he settled on a degree in pharmacy in order to support his new family.

Unfortunately, the marriage didn’t last, but it resulted in three beautiful children whom Massoud takes great pride in. Today, two have become success stories in their own right: one as a dentist and the other a contractor. Massoud’s youngest still lives at home with him while completing school.

Massoud says that the series of events that brought him to St. Adolphe as the local pharmacist were both coincidental and serendipitous, and he hasn’t regretted the decision even once.

The building where his business is located comes with a rich history, just like Massoud. Many years ago, it served as a community school. There are still remnants of this aspect of its history in the attic where schoolbooks lay dormant, placed there for their insulative properties.

Eventually, the building turned into a grocery and liquor store, and later a pet grooming facility.

Massoud says that from the moment he opened his pharmacy doors, the community has embraced him.

“This is my second family,” Horriat says of St. Adolphe’s residents. “Honest to God, it’s an honor and a pleasure to be here. Everybody knows me, they accept me, and I love every single one of them.”

French was one language Massoud never learned to speak, but his lack has never deterred his French-speaking patrons.

For nine years now, Massoud has enjoyed the quick commute to his second home, St. Adolphe, and doesn’t imagine retiring anytime soon.