A distinctive feature of older rural neighbourhoods is the shared well. Though wells may soon become a thing of the past here, unless you live in a newer development you are likely still connected to one.

Not every lot has a well. In most circumstances, wells are shared by multiple neighbours and typically located on one property, along with a pump. That homeowner is billed for the electricity to run the pump. It is normally their responsibility to maintain the pump and collect the cost of hydro from their neighbours.

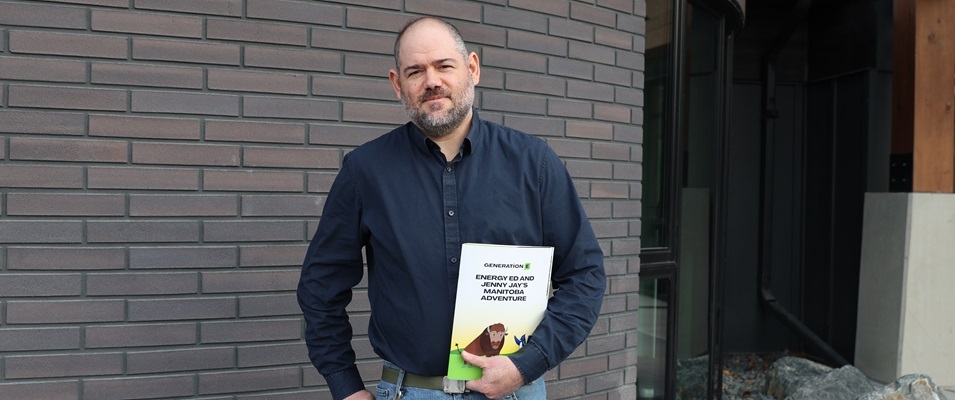

Well agreements are a common and important part of shared wells. According to Ron Janzen, lawyer at Smith Neufeld Jodoin, this kind of agreement is mostly about common sense.

“[The] risks, as I see them, of multiple homeowners sharing a single well would be similar to the risks of neighbours sharing almost anything [like] lawnmowers, fences, etc.,” says Janzen.

He recommends that a formal agreement, registered at the Land Titles Office, is always a good idea. And like any agreement, it should be formalized before problems arise and while all parties are on good terms.

What are the risks of not having one? One example might be a neighbour who uses a lot of water for watering lawns, filling swimming pools, flooding backyard rinks, or filling cisterns to take to the cottage. When the cost of running the pump is shared by numerous neighbours, and one neighbour’s water use is exceptionally high, should everyone pay?

And what happens when pump maintenance or repairs are required? How will all the parties agree on the costs of repair and whom to hire?

When looking to buy a home with a shared well, Janzen suggests that buyers should consult a lawyer before entering into the offer to purchase or make the offer subject to their lawyer’s approval. Lawyers should be made aware of shared wells or well agreements in order to properly advise their clients. The buyer needs to know whose property the well is on, if the agreement is registered with the Land Titles Office, and if so, what it says. Many lending institutions require a registered well agreement as a condition of financing.

“What if the shared well agreement is a simple agreement that was scratched out between two neighbours many years ago, and never registered at the Land Titles Office?” asks Janzen. Such an informal agreement is virtually useless, he says. Should problems arise between homeowners, such an agreement is not legally binding.

When major well disputes between homeowners ensue, the homeowner with no well on his property is left with few choices. One option may be to drill his own well, a cost that could run in the $4,000 range. Legal litigation is another option, the costs of which could easily surpass the first, in addition to the stress and time involved with legal processes.

An informal agreement can also create problems when one homeowner decides to sell. Without a registered well agreement, a sale could fall through. In such cases, will the seller assume the legal costs on his own to provide one? Will the other homeowners contribute to the cost when they aren’t benefiting from the sale?

What should a registered well agreement include? Janzen says it should clearly state the location of the well, whether it’s on a boundary or someone’s property. It should indicate which properties require access to other properties if maintenance is required on the lines. It must clearly state which homeowner receives the electricity bill and how the costs will be shared. And finally, it should specify how the costs of maintenance and repairs will be distributed.

“Having a well agreement does not guarantee quality, quantity, or potability of water,” says Janzen. “Well water should be routinely tested for potability. Pressure systems, softeners, and other treatment systems vary, and local Niverville plumbing companies are very familiar and capable of dealing with these issues. If the town eventually requires everyone to hook up to town water, perhaps eventually the importance of private well agreements will ‘dry up.’”