For nearly a year, a battle has been waging in the city of Winkler, and the local public library is at the heart of it.

On the offensive is a group of passionate parents who are facing off with their city council, demanding that they deny funding to the South Central Regional Library (SCRL) which oversees branches in Altona, Manitou, Miami, Morden, and Winkler.

The reason, they argue, is that the SCRL has declined to remove children’s books from their shelves that fall into the category of sexual and gender education.

The parent group claims that their motive is not censorship but rather to have the books removed on the basis that they represent pornography.

The Books and the Arguments

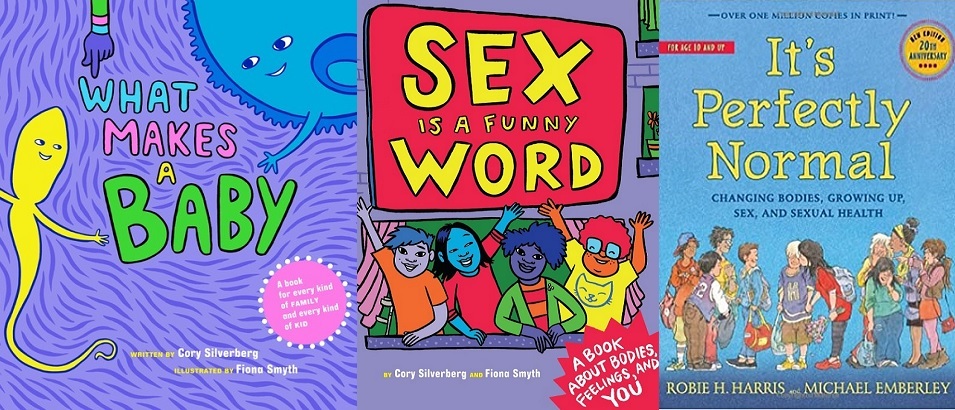

The specific books under fire include two written by award-winning Canadian author Cory Silverberg called What Makes a Baby and Sex Is a Funny Word. The first is written and illustrated with young children in mind and the topic of intercourse is not discussed in its pages.

The second, illustrated in comic book style, is intended for a slightly older audience and covers topics such as gender differences and establishing boundaries for touching.

Finally, the third book, called It’s Perfectly Normal: Changing Bodies, Growing Up, Sex, Gender, and Sexual Health, was written by award-winning children’s author Robie H. Harris for pre- and early teens.

First released more than 25 years ago, Harris’s updated version now includes current topics such as abortion, sexual abuse, and how to stay safe in an online world.

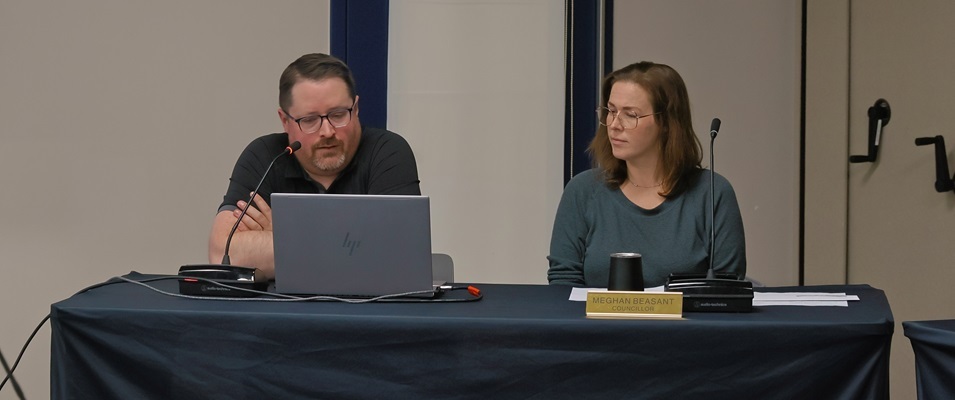

Winkler resident Karin Banman has been a vocal advocate for the parent group from the beginning. Frustrated with the SCRL’s decision to keep the books on their shelves, even though they are kept in the age-appropriate sections, Banman attended Winkler council’s budget public hearing on March 14 to plea for a SCRL defunding.

She also presented a petition with over 1,700 signatures from local residents who concur with her resolution.

“To keep books such as these in the library is to create an unsafe environment for children and to place them at undue risk,” Banman told council.

A second resident, also referencing the books as porn, took to the podium presenting council with an alternative to defunding.

“Withholding money in order to achieve a purpose creates conflict,” he said. “The library that we have here in Winkler is a very valuable place for a lot of people… I do want all of us to be careful when we demand something that maybe will come back to haunt us.”

An alternative, he said, would be to require the local library board to implement a policy change so that books containing sexual content need to be signed out by an adult. Encouragement to do so would need to come from council.

According to one news source, Winkler’s mayor took that to heart, sending a request to the SCRL board to review their policy on how books like these are displayed. The board has until the end of this month to respond.

A Local Regional Library and HSD Weigh In

Without a doubt, library directors across southern Manitoba have been watching the spectacle with rapt attention, wondering if the movement will come this way.

The Ritchot library director declined comment to The Citizen on the subject. But Chrystie Kroeker Boggs, library director for the Jake Epp Library (JEL) in Steinbach, had a few things to say.

“I haven’t personally seen or read the books that are being challenged in Winkler, so I won’t make a statement on those three specifically,” says Boggs. “However, I wholeheartedly support the Canadian Library Association’s statement on intellectual freedom and believe it to be imperative that public libraries make information of all legal forms available to patrons. I support SCRL’s similar stance and the effort they’re putting in to ensuring the members of their community have pertinent resources available to them. Freedom and access for one group means freedom and access for all groups.”

Boggs adds that the books being challenged in Winkler aren’t stocked at the JEL but would be considered, like any other special request, if someone were to ask for them. Other age-appropriate materials pertaining to the human body and sexuality are carried in their juvenile non-fiction section, aimed at readers from eight years old and up.

An administrative team looks after the acquisition of new books for the library shelves. To help guide their decision-making process, Boggs says they consult reviews from verified sources and other libraries as well as take into consideration the reputation of the publisher who stands behind the written material.

They also adhere to a Collection Development Policy created specifically for the JEL.

“The presence of an item in the Jake Epp Library’s collection is an affirmation of the principle of intellectual freedom,” the policy states. “The following will not cause an item to be removed or excluded from the collection: race, religion, nationality or political views of an author, frankness or coarseness of language, controversial content, endorsement or disapproval from an individual or group.”

The superintendent of the Hanover School Division (HSD), Shelley Amos, says that the responsibility of book selection for school libraries in the division falls to the personnel within each school, although the school may look to the public or the division for recommendations.

Even so, she says, significant care is taken to make sure that materials are presented in ways that will match the child’s age and emotional maturity, among other factors.

“The selection of learning resources on controversial issues is directed toward maintaining a balanced collection representing various views,” Amos says. “The input of parents in these matters is welcomed. However, no parent has the right to determine reading, viewing, or listening matter for students other than their [own] children.”

The Protection of Intellectual Freedom in Canada

Endorsed by the JEL and libraries across the nation are the principles laid out by the Canadian Federation of Library Associations in its statement on intellectual freedom and libraries.

The statement states: “Libraries have a core responsibility to safeguard and facilitate access to constitutionally protected expressions of knowledge, imagination, ideas, and opinion, including those which some individuals and groups consider unconventional, unpopular or unacceptable. To this end, in accordance with their mandates and professional values and standards, libraries provide, defend and promote equitable access to the widest possible variety of expressive content and resist calls for censorship and the adoption of systems that deny or restrict access to resources.”1

What Local Parents Say

The Citizen put out a call to local parents to share their opinion regarding public library availability of children’s books on sexuality and the human body.

Some parents voiced support for the decision made by the SCRL.

Another agreed but felt restrictions on books pertaining to sex and the human body were needed. This parent requested anonymity given the sensitivity of the subject. She is the mother of middle-school-age children.

“In my opinion, these books should be in the adult section of a library, where an actively curious preteen would still be able to find them but would remove the chance of a child who is not ready to be exposed to them,” this mom says.

She admits to not appreciating books on sexual education targeted at children but doesn’t believe in banning them either. Their placement in a library, she says, is crucial so that children who aren’t ready won’t be unnecessarily exposed.

“These books teach one perspective, and it is not one that is accepted by all,” she adds. “I personally want to be able to have open conversations with my kids about sex and relationships and I don’t want them to read a book like this without being aware [first].”

Rebecca Bilsky says that she wants sex education for her kids to be different than it was for her as a child. For Bilsky, sex education focused primarily on warnings not to get pregnant.

“I have a nine-year-old boy,” Bilsky says. “I would absolutely prefer that my kid secretly went to the library and read one of those books without me knowing than secretly went on the internet to find God knows what. Or talked to other kids on the playground.”

Bilsky borrowed the book It’s Perfectly Normal from her public library about a year ago and used it as a tool to discuss sexuality with her child.

“As well as consulting experts in health, the [author] consults other voices in the sex ed conversation [too], including religious leaders,” says Bilsky. “I was surprised and impressed. That seemed to me like a very accommodating inclusion.”

Another benefit of using the book as a parental tool, she adds, is that it opened up conversations about things she’d never thought about, or was experienced in, like risk management of sexually transmitted disease.

Jessica Galli is a mom to three children under four years of age.

“I think it is extremely important for children to learn all parts of the body and how it functions,” Galli says. “These ‘sensitive’ topics need to be shared with our children so they are aware. It is better that they have literature they can understand along with parent-provided information rather than finding out this information through different channels that may not provide accurate details. The alternative channels do not educate on the relationships and do not provide information on consent and healthy bodily habits and relationships.”

Sara Dacombe’s kids are 11 and 14. She’s been following the news regarding what’s happening in Winkler and has heard that similar parental requests for the removal of books from public libraries are growing in this area as well.

“The book-banning requests that have escalated in southern Manitoba are very concerning to me,” Dacombe says. “Censorship of regional public libraries is wrong.”

She says she understands that many parents are just struggling to try and maintain their child’s innocence in a world with overly sexualized messaging all around them.

“Learning about sex does not make children less innocent,” she argues. “It does, however, keep them [from being] naive and unsuspecting. To that point, there is an overwhelming amount of research supporting how sex ed keeps kids safer from exploitation, reduces the age of first sexual experience, and drastically reduces teen pregnancy.”

Dacombe says that, by the time a child encounters these kinds of books within their age-appropriate section of the library, those conversations should already be happening at home.

“If our children encounter information outside of what they are developmentally ready to understand, which is unavoidable in any healthy societal context, it is a parent’s responsibility to facilitate a relationship with their children in which the child can ask questions and receive good information,” she concludes. “If the parent relationship is insufficient to provide this, I am in full support of children asking questions and receiving good information from another appropriate role model.”

The Book-Banning Phenomenon South of the Border

Since the summer of 2021, the demand to ban books in American libraries and schools has grown into a full-on movement that’s sweeping across states like Texas, Florida, Missouri, Utah, and South Carolina.

This literary culling, dubbed “wholesome bans,” began as a grassroots movement led by parent groups.

PEN America is an advocacy group established in 1922 to protect literary freedom of expression.

“We champion the freedom to write, recognizing the power of the word to transform the world,” PEN America’s website states. “Our mission is to unite writers and their allies to celebrate creative expression and defend the liberties that make it possible.”2

Alarmed by this recent drive to ban books, PEN America has been closely tracking how the movement has affected America’s literary world over the past two years.

From July 2021 to June 2022, PEN America lists 2,532 instances of individual books being banned, affecting 1,648 unique book titles. In the six-month cycle following, they say, that number has climbed exponentially.

Not surprisingly, 22 percent of the book titles removed from library shelves in the first wave were those containing sexual content of one form or another. These included stories containing details on sexual experiences, stories about teen pregnancy, sexual assault and abortion, as well as non-fiction books on puberty, sex, or relationships.

Battle cries have echoed out over what these groups were calling “pornography geared towards children.”

Another 41 percent of the books banned during that period had LGBTQ+ themes or characters in the story who identified as LGBTQ+ or transgender.

Books with themes revolving around race or racism, or feature characters of colour, are also among those being culled from many public libraries in some U.S. states. These include memoirs and autobiographies.

According to BBC News, a Florida school removed 16 books pending review, including award-winning novels such as The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini and Beloved by Toni Morrison, citing obscene content.3

A school district near Seattle removed Harper Lee’s classic novel To Kill a Mockingbird from the curriculum for its racial themes and use of racist language.

“The full impact of the book ban movement is greater than can be counted, as ‘wholesale bans’ are restricting access to untold numbers of books in classrooms and school libraries,” the PEN America website states. “This school year, numerous states enacted ‘wholesale bans’ in which entire classrooms and school libraries have been suspended, closed, or emptied of books, either permanently or temporarily. This is largely because teachers and librarians in several states have been directed to catalog entire collections for public scrutiny within short timeframes, under threat of punishment from new, vague laws.”