“What do you do for a living?” Whether you’re meeting someone for the first time or making small talk with your barber, this is a question we spend most of our lives answering. For most of us, the answer is straightforward. For others, their job is more than a title; it’s a story. Over the next few weeks, The Citizen will introduce you to locals whose careers break the mould—jobs that are rare, remarkable, and sometimes even dangerous. Let’s meet them together.

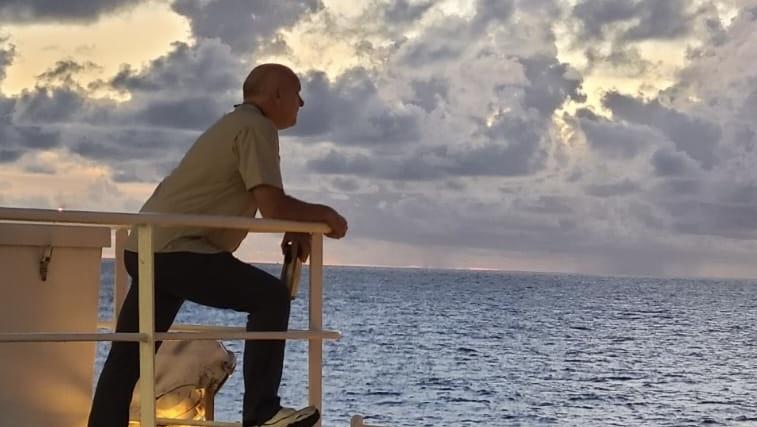

Barrie Sylvestre of St. Adolphe works in the field of land and marine seismic exploration. For those unfamiliar with seismic exploration, it’s a sophisticated means of locating subsurface hydrocarbon reserves—and it’s an important part of operations for oil and gas companies.

Within this context, Sylvestre works as a health, safety, and environmental quality control (HSEQC) consultant. His team of quality control personnel can be sent almost anywhere in the world to oversee the work of on-site contractors.

“I just want to make sure that, at the end of the day, everyone goes home with all of their fingers and toes,” Sylvestre says. “I’ve seen some accidents, and we’ve had to airlift some by helicopter to emergency.”

Sylvestre’s job takes him away from home for weeks or sometimes months at a time. At the time of this interview, Sylvestre was in northern Alberta, getting ready to leave for South America.

He’s been at this job for the better part of 35 years. In total, he says that he’s worked on sea and on land in more countries than he can recall.

Seismic research itself is fascinating to Sylvestre. Whether done from land or water, the goal is to identify potential oil and gas reservoirs beneath the earth’s surface.

“We do two-dimensional, three-dimensional, and four-dimensional seismic research,” Sylvestre says. “Two-dimensional would be like an X-ray of the subsurface of the earth. Three-dimensional would be like an MRI.”

The fourth dimension, he says, involves the use of timelapse images to get an idea as to how oil reservoirs shift and move.

Researchers also use sound-sensing devices to find potential oil sources. Land-based devices are known as geophones, and in water they’re called hydrophones.

“On land, we place geophones at predetermined locations in a grid pattern,” Sylvestre says. “They make a sound at [specific intervals] and the sound penetrates through the earth’s crust. Then the sensors pick up the reverberations at different frequencies and collect the data. The data is put into a computer and then you have your final results.”

Twenty Years on the Seas of Southeast Asia

While many people aspire to specific career paths from a young age, Sylvestre wasn’t one of them. In fact, most of his career was the result of a series of fortuitous events.

As a child, he grew up on a small farm in Saskatchewan. He studied history in university and eventually picked up a job in Ottawa working for the federal government as part of Canada’s museums. That work took him all over the country.

“I was living in Ottawa, and in 1989 I went to Thailand just to travel for six weeks,” says Sylvestre. “In 1990, I quit the government job with the intention of travelling [abroad] for a year and I ended up staying there for 20 years.”

Sylvestre took a job as an English teacher in Jakarta, Indonesia, but the pay was poor and he wanted something more.

One night in a bar, he found himself sharing with an acquaintance that he was looking for work.

Ironically, the acquaintance had just quit his job in the oil and gas field. He gave Sylvestre his former employer’s business card.

Sylvestre made a phone call to Singapore and quickly connected with the employer. As fate sometimes dictates, this gentleman had also been born and bred in Saskatchewan.

“He says to me, ‘You’re a good old boy from Saskatchewan, a farm boy. If you want a job, be here in a couple of days and we’ll get you set up.’ I had no idea what I’d be doing. I’d never heard of seismic research before.”

Sylvestre was trained on the job. His first posting was to a vessel off the coast of Australia. Little did he know that he’d spend the next 20 years working on seafaring vessels like this one.

On-the-job training was the modus operandi for many companies in the 1980s. But today, Sylvestre says, the seismic research field requires engineering- or science-based degrees.

He began his career as a basic helper, on hand to do whatever needed to be done.

“On my first week being on board a vessel, we were running away from a cyclone,” Sylvestre says with some mirth. “I was like, ‘What the hell am I doing here?’ We were in rough seas and it wasn’t a big vessel by any means. We were just getting tossed around.”

He stuck with it, though, and he’s glad he did. Back in those days, he says, the men worked together as a brotherhood. There were no cell phones or computer screens to distract them. Communicating with family on shore was cumbersome, so they had to rely on each other.

“We had one TV and a VHS machine and everyone would pile into [one room] and watch a movie. It was a bonding experience. And it was fun!”

Sylvestre recalls some hair-raising moments when the crew wasn’t sure whether they’d make it back to shore alive.

It wasn’t that they didn’t have the ability to forecast a coming storm, but the speed at which a storm moved could make all the difference. Their vessels were always pulling research equipment and tethered to literally miles and miles of line that had to be reeled in before evacuation was possible. That process could take upwards of seven hours.

On one occasion, they didn’t get the job done fast enough.

Sylvestre was at the stern of the ship along with three others. Two of them were clipped onto the vessel at its tail, reeling in the line and equipment. Sylvestre was calling out the waves, warning whenever a big one was coming.

“I see this wave coming and I’m standing beside a pole. The guy who’s running the hydraulics is at another pole. I yelled out, but the wave that came in was bigger than we anticipated. I’m holding onto the pole when this wave hits and I went horizontal. I look over, and the hydraulics guys is holding onto a pole and he’s horizontal. The two guys who were on the lifelines got swept into [the sea]. It was almost cartoon-like. It was just surreal.”

Thankfully, he says, there were no fatalities that day. However, he’s heard of circumstances when others weren’t so lucky.

As time passed, Sylvestre worked his way up the ranks. He was promoted to support vessel coordinator, which made it his job to teach crews about the safety aspects of running support vessels.

Eventually he was head-hunted by a large company and offered the job of safety officer, which he’s still doing today.

During his years in Indonesia, Sylvestre met his wife Jasmine, who also worked in the industry and understood the nature of this job that required him to be absent so much of the time.

In 2010, he and Jasmine made the move to St. Adolphe where his father and two brothers already resided. In 2014, Jasmine received her permanent residency. She now works for Gilles Lambert Pest Control.

“She loves the cold more than I do,” he says. “In the wintertime, you can dress up. In the tropics, you can’t dress down enough to stay cool. So that’s why she just loves it here.”

In 2023, Sylvestre’s father turned 100 and he was glad to be there for the big family celebration.

Today, at 62 years of age, Sylvestre is just beginning to think about retirement.

“I’ve still got some gumption in me. But at the same time, as we speak, my wife is in Bali looking for a parcel of land.”