Staff and students of Niverville High School (NHS) believe there’s much to be learned through community and traditional cultural practices. That’s why, for the third year in a row, they’ve marked the winter solstice.

The winter solstice falls annually on a three-day period preceding Christmas: December 20–22. It’s the time of year when the northern hemisphere experiences the shortest period of daylight and longest nights of the year.

Many cultures observe the winter solstice with festivals and rites, viewing this annual event as the symbolic death and rebirth of the sun. Some ancient societies erected monuments, such as Stonehenge, to align with the sunrise or sunset during the solstice.

Staff members Raelyn Voulgaris and Katie Martin have been strategic organizers of NHS’s annual winter solstice celebration.

Keeping to the theme carried over from previous years, the NHS version of this celebration includes an appreciation for the multicultural nature of the school’s student body, with a special focus on Indigenous teachings.

With that in mind, December 19 at NHS was day of self-reflection, slowing down, pondering the past, and looking forward to what the future may hold.

“It’s meant to reflect on how the year went and set good intentions for next year,” Voulgaris says. “[That includes] a lot of self-care. What does that look like for you? Is that reading a book, drinking some tea, doing an activity that brings you joy? So that’s the whole point of today, just to slow down, be together, and tell stories.”

If these teachers have learned anything from previous school events, it’s that they should be carried out by the students, not for the students.

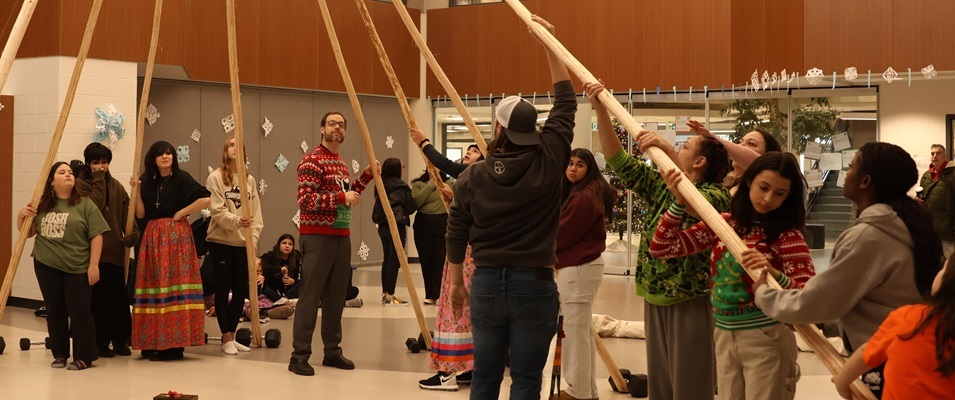

So on Thursday morning, the day’s celebration began with the erection of an 18-foot teepee in the school’s multipurpose room by any student willing to participate. The handcrafted teepee was a parting gift to the students from outgoing principal Kimberley Funk. Under the instruction of Patti Sayies and her daughter Holly, the teepee was erected by students for the first time this year.

Once constructed, Sayies and her daughter led each classroom in teepee teachings derived from their Indigenous heritage. Sayies’s expertise has also been an integral component in the school’s Ribbon Skirt Club, which seeks to understand Indigenous teachings through hands-on skills such as sewing, beading, and leatherwork.

Sayies says the winter solstice is one of the four most important events in Indigenous culture. It’s recognized as one of the few times of the year when the hectic pace of life is briefly paused. Stories are told, community is celebrated, and artistic endeavours are embraced.

“When we hold a winter solstice ceremony, it usually starts with a pipe ceremony where we share and talk about the past year,” Sayies said. “It’s a time of tears and it’s also a time of laughter.”

Similar to Indigenous tradition, a fire ceremony was held outdoors at NHS for students to gather and share, symbolically leaving their hopes and good intentions in the embers.

Keeping to the theme of community and sharing, the student body, staff, and family members were invited to join in a noon feast. Students participated in food preparation prior to the celebration while others brought traditional dishes from home.

The afternoon revolved around yet another Indigenous solstice tradition: gift-giving.

“Everyone was invited to bring a gift to give away,” says Voulgaris. “The whole point of this [gifting] is actually to teach kids to be less materialistic. That’s an Anishinaabe teaching and it’s meant to just remind us that you don’t need to purchase a gift to bring joy. It’s typically something that’s handmade or it’s something that no longer serves you.”

Martin’s students prepared for this tradition in advance, having learned how to harvest red willow which they crafted into wreaths. Red willow is used prolifically in Indigenous cultures for both its medicinal value and usefulness in making hoops for hoop dancers.

Jay Hoare, a Grade Eleven student who is especially fond of the school’s winter solstice celebration, comes from Cree and Metis ancestry and is a volunteer teepee caretaker.

“My family doesn’t talk much about our history,” Hoare says. “Once I came to Niverville High School, that’s when I started really learning and getting into my history.”

Teepee Teachings

Thanks to the wisdom shared by Sayies and her daughter during the teepee teachings, students came away from the experience having learned that there is much more symbolism in the teepee than first meets the eye.

Historically speaking, the teepee would have been constructed by the women of the tribe. It stands to reason that the structure in its entirety is said to be fashioned like a woman in a skirt.

Each individual component holds deep maternal meaning. The 13 spruce poles that make up its bones represent the 13 annual cycles of the moon, corresponding to the 13 annual cycles of the female.

Each pole is named for its important role in creating a home: respect, humility, faith, kinship, thankfulness, and sharing, to name a few.

The rope used to bind the structural poles together is known as the umbilical cord and the nine pegs used to fasten the canvas opening of the teepee are representative of the nine months during which a mother carries her child in utero.

The teepee opening always faces the east. where the sun rises and, symbolically, new life begins.

The teepee is about much more than symbology. It’s also a sophisticated structure which incorporates both mathematics and physics into its design, making it an incredibly sturdy home.

“If you were in a regular tent, it would most likely blow away in a really bad windstorm,” Sayies said. “This actually gets suctioned further into the ground [in those conditions], so it’s an amazing structure.”