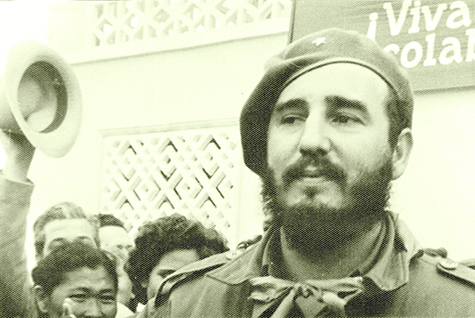

The world has truly lost a great leader in the death of Fidel Castro. This greatness is unarguable, for by greatness I mean charismatic leadership and creation of change. What will likely be debated is whether the good of the man, the good of his actions, outweighed the bad. And, as is often the case, determining this tally may lead to a study of the alternatives, those that were and those that could be.

Most immediately, we have a typical Western democracy reaction to the political system under which Cuba has been governed for the past 50-plus years. The disdainful rhetoric for socialist ideology (including actual communism) makes it difficult for many people to see the complex situation that was (and is) facing the region, and consequently see deeper into the man who not only transformed Cuba but became a catalyst for change throughout Central and South America.

There is additionally a very Canadian connection, as this situation helped in earlier years to establish and clarify our foreign policy in a way that was independent of our American neighbours and British colonial leaders. While often credited to Pierre Trudeau, this foreign policy shift actually began with Conservative Prime Minister John Diefenbaker. Dief the Chief is often accused of puppeting American policy, yet his decision to not immediately back Kennedy during the Cuban missile crisis created an opening for Canada, while respecting American might, to stand on its own two feet. Without this break, the uniquely Canadian position established by Trudeau may not have been possible. This was unpopular, nationally and globally, and would haunt Diefenbaker for years. And it was surprising, given his open disdain for communism and the Soviet threat of the time, for he saw parallel evils in the Soviet conquest and American colonialism of Latin America. Perhaps it was this comparison that allowed him to see past the threat of a Soviet world order—or, as some say, it may have been pure indecisiveness of a man torn between two evils.

When Trudeau entered the scene, he came with a more moderate view. He still saw the evils of the communist regimes, but he could appreciate the moderated stance of Castro himself, who was tied closer to nationalism than communism. While ultimately steering Cuba toward communism, Castro never embraced, nor was he motivated by, Marxist ideals. His nationalist agenda drove the revolution, and his pragmatism required that he partner with the socialist rebels to ensure victory against the corrupt American-backed government of Fulgencio Batista. Indeed, it can be argued that the American embargo to follow backfired, since it solidified the Soviet Union as an economic support in Cuba.

Nationalism is independent of political stripe and is simply defined as the ability of a people to control their own destiny and economics without interference from outside parties. Malcolm X also spoke heavily of nationalism as the answer to the challenges facing African-Americans in the lead-up to the 1964 U.S. elections.

As Canada broke from the American norm on foreign policy, perhaps the ideology of independence and exercising control of one’s own affairs helped create a brotherly connection between the Canadian and Cuban people and their leaders.

Nationalism, put in the proper context of a true and just system, is an empowering and uplifting philosophy. Who can argue that it is the right of all people to enjoy this freedom of thought without interference, or subtle duress, from outside sources, whether that be other countries or internal social groups? When a community or country controls its own economics and politics, it keeps control of its money and resources rather than seeing it siphoned off. As was the case in Latin America (and still is, to some extent), political and financial interests were skewed to benefit the U.S., and why not? Any entity, political or otherwise, would be foolish not to be self-serving—putting aside ethics, of course, and political agendas, regardless of rhetoric, are not driven by ethics; they are driven by economics.

So in context, we see the complexity of the situation in the persona of Fidel Castro. Perhaps when the dust settles and change continues to come to the Cuban people, we’ll better see the patriotic motivations behind his embrace of nationalism. And perhaps we’ll better understand his pragmatic concessions, while still being able to critique the challenges and wrongs they led to.