Throughout rural Manitoba, one-room schoolhouses used to dot the landscape. About 70 years ago, at their peak, there were more than 2,500 such schools on record in the province, and several generations of Manitobans got their start in life in these classrooms. Anyone who’s older than 60 years old likely has some vivid memories of attending a one-room school.

It was a memorable era, a time when our parents and grandparents dutifully walked to school each day, uphill both ways, in bare feet, with their bucket lunch kits full of homemade sandwiches and honey treats.

It’s an educational experience most students today, accustomed to air conditioning, locker-lined corridors, and large student bodies, wouldn’t recognize.

Governance

Although Manitoba’s Department of Education has always been responsible for the administration of education, the governance of each individual schoolhouse was the purview of a locally elected board of ratepayers. This board was responsible for hiring teachers, levying taxes to provide their salaries, and making sure the school buildings themselves were kept in good working order.

There were often economic disparities between schools. For example, poorer districts had more trouble collecting taxes. In cases like these, school districts would have to apply to the Department of Education for grants to help cover their costs. In certain instances, they would be forced to hire teachers with less experience, to lower the salary.

However, the Department of Education was responsible overall to train teachers, provide core financing, set the curriculum, and ensure that teachers were competent and could follow the syllabus for each grade level, as set out by the province.1

To keep track of the state of these one-room schoolhouses and make sure they were being kept to a high standard, school inspectors were appointed by the province to service a particular geographic area and visit each school a few times a year and report on it.

In addition to reporting on the schools and the quality of instruction there, these inspectors sometimes hosted training days or summer sessions for teachers. They also worked to ensure that the schools encouraged healthy living and kept their properties in good condition.

A book by John Lehr and David McDowell, Trailblazers, records that in 1946 school inspectors made around $2,400 per year.

Bilingualism and Consolidation

In 1916, Manitoba’s governing elite—mainly English Protestants—feared that bilingual schools would eventually lead to balkanization, the process of a larger region or state breaking up into smaller regions or states. This resulted in a change from a bilingual school system to a unilingual system—English only.

At the time, there were a relatively small number of bilingual schools (276) compared to the much larger number of unilingual schools in the province (more than 1,200). In fact, there were large areas completely devoid of bilingual schools.

Lehr and McDowell wrote about the abolishment of Manitoba’s bilingual school system, calling it “a casualty of patriotic fervour inflamed by Allied propaganda and driven by resentment of special privileges given to Mennonite conscientious objectors and enemy aliens from Austria–Hungary. A good dose of anti-Catholic and anti-French prejudice also helped to seal the fate of bilingual schools in the province.”2

One local woman, Claudette, has a vivid memory of this period of time. Despite the province having abolished bilingual schools when she was a girl, her teacher still snuck French books into the hands of students.

“I remember we had to hide our French books when the inspector would come around,” says Claudette.

Bilingual schools were re-established in 1971, after the Royal Commission on Bilingualism in the 1960s.

The Commission had been established to research the existing state of bilingualism and biculturalism in Canada. Initially intended to address the question of French language rights, the Commission also examined cultural contributions of other ethnic groups.

The Pierre Elliott Trudeau government then adopted multiculturalism as an official state policy, becoming the first country in the world to do so.3

In the 1950s and 1960s, rural schools were consolidated, marking the end of the era of one-room schoolhouses. During this transitionary period, local ratepayers approved the closure of schools and afterward students were bussed to larger schools in urban centres.

This consolidation of one-room schools mainly occurred due to the improvements in the provincial road infrastructure and network. Transportation by bus became more feasible over longer distances.

Parents were concerned about their children having to travel further away for school, but they were assured there would be better educational opportunities at the consolidated schools.

Not all one-room schools were immediately consolidated, however. One of Manitoba’s last one-room schoolhouses—Mason School No. 2149 in the Rural Municipality of Stanley, south of Morden—only closed its doors in 2002.4

The Teachers

In 1910, three-quarters of all schoolteachers in rural Manitoba were female. In the mid-1930s, this changed slightly, but not enough to make a significant difference—and the gender divide led to teachers having a lower salary scale overall compared to other professions.

However, it should be noted that teaching was viewed by the immigrant community as being an elite profession, because teachers invariably became spokespeople and representatives for their particular cultural groups. From there, teaching often served as a path into more lucrative careers, like law or medicine, and away from manual labour.

The majority of teachers, being young, single, and female, received their training at Manitoba’s Normal School, graduating with third-class, second-class, or third-class teaching certificates. Teachers could start their careers with third-class certificates, if they still lacked training in some Grade 12 subjects. To advance further, however, they needed to complete additional studies through summer or university courses.

From the 1920s to the 1940s, the Normal School’s curriculum included instruction in citizenship, classroom management, English literature and grammar, social studies, physical education, nature study, and music. Practice teaching was carried out in model classrooms and in neighbouring schools in Brandon.

Interestingly, after World War II, there was a shortage of teachers. However, married women didn’t return to the profession because it wasn’t culturally acceptable. Women were only supposed to fill these vacant positions if they had been widowed.

In addition to curriculum duties, supervising children, filling out report cards, and conducting home visits, teachers made reports for the school inspectors that summarized what each grade was doing at any given time. Most grades ended up learning the same materials, especially in the subjects of science and the arts. It was the only way for most teachers to efficiently handle the multi-grade classroom.5

“Teaching was plain and simple,” says one teacher, Susan. “We had to teach a variety of grades, depending on the books we had. We assigned work from there. Extra explanations and projects… there wasn’t as much of that as there is now.”

But was it so plain and simple? Teachers had to look after more than the assigned provincial curriculum. For example, they would supervise the process of kids getting their immunizations—a part of the job their students typically didn’t much look forward to.

“St. Adolphe School was a one-room schoolhouse at the corner of Highways 311 and 200,” says Ellen. Today, that same property is home to the Whitetail Meadow event centre. “When the public health nurse used to come to give immunizations, the teacher would go and meet her at the entrance of the school. Students who hated needles would sneak out the windows and run away.”

The teachers also provided instruction and organization for field days, nature days, outings, natural class, arts and music, Christmas concerts, spring concerts, and local drama productions and debates. Teachers also had to supervise kids during the lunchtime recess and all outdoor play.

“We did Christmas concerts based on religion, with Christmas carols and nativity scenes,” says Susan. “We also did different plays. I sewed an angel once. Teachers were responsible for all of that.”

“I loved it when we had Christmas concerts at school,” says a former student, Lorraine. Clearly not all aspects of her school’s Christmas concerts were religious in nature. “The highlight was when Santa would appear at the end and give them a paper bag with an orange in it.”

Teaching salaries fluctuated. In the late 1920s, teachers made between $720 and $900 per year. The exact amount was dependent on which local school district a teacher worked for.

However, the Great Depression impacted these salaries, bringing the average down to just $430 per year.

The pension movement actually began during the Depression era. In 1934, teachers started to receive a pension in the form of a retirement deduction, usually $4.80 per month.

Teachers often lived in the nearby teacherage, a small house or cottage within walking distance of the school. If they did so, they were usually also responsible for heating the schoolhouse in the winter months.

If the teacherage was far from an actual town, teachers were known to catch rides on Eaton’s delivery trucks. Either that, or they’d have to walk for miles to get around or hitch rides from neighbours.

“I taught in a one-room schoolhouse from Kindergarten to Grade Nine,” another teacher, Vern, recalls. “I remember arriving and thinking we were in a very isolated place. It was cold and the middle of winter—I was greeted by a loaf of bread, half a cherry pie, and one antler from a recent white-tailed deer kill.”

They had to teach anywhere from eight to 44 children for 200 days of the year. Whatever the situation, managing so many students of different ages presented a complicated challenge—especially when it came to troublemakers.

“The boys were teasers and would taunt the teacher sometimes,” says Martha, now 99 years young. “One time, one of the boys stole the strap and ran across the road to bury it in the field… Once the teacher, Rose-Anna Rioux, found out the strap was missing, she was livid. She insisted on finding out who the culprit was. No matter how much she persisted, none of the kids would tell her. Not even the young ones.”

In this particular classroom, there were 32 students from Grades One to Eight, and Martha says they were all very loyal to one another. Not only that, but they were happy to know the strap was gone!

“The teacher intended to keep the kids at school till one of them would tell her where the strap was,” Martha says. “Around suppertime, her husband, Michel Desrosiers, came by the school to see why his wife had not come home from school yet. He was surprised to see all the students still in school. Even after his wife explained what was going on, he told her to give it up, because at this point the kids were surely not going to tell her where the strap was or who took it.”

Oriole, who taught in a one-room school, has many memories of student shenanigans. One day, while writing on the blackboard, she heard a noise coming from outside the school. Curious, she went out into the yard to see what was going on.

“A couple of boys were into mischief already,” says Oriole. “I rang the bell and all the students came back, but you could see a cloud following this patch of boys. They were smoking and trying to hide it. They thought I didn’t notice.”

That certainly wasn’t the only occasion she had to deal with such troublemakers.

“One time I was riding my bike back to the teacherage and I had to go down a steep bank and up the other side,” she adds. “Halfway down, I was speeding and got a terrible pain on my side. I hung onto the handlebars as best I could and got to the bottom and took my sweater off. A bumble bee flew out! I found out the next day that [a student] had put it on my desk, and it had crawled and hid in my sweater.”

She also remembers almost being hit by a ball that a student threw right through one of the school’s windows—it sailed through the glass and missed her by an inch.

“In winter time, I used to teach my students to square-dance at recess,” Oriole says. “You either kept your class busy or they kept you busy.”

The Schoolhouse

Many one-room schoolhouses were built based on a blueprint supplied by the provincial government—although this wasn’t always the case, particularly if local ratepayers had a hand in the construction or provided building materials.

The schools usually had one room—or, in some cases, two. They had a woodstove, no plumbing (at least until electrification came into effect during the 1950s), and were furnished with a blackboard, desks, a bell, and a few pictures of the British royal family.

Interestingly, Ukrainian schools had a picture of Taras Shevchenko, a famous poet and artist.

The first task of a teacher was sometimes to start the fire and warm up the schoolhouse if there was no local caretaker. This task might also be assigned to a senior male student, whose job it would be to fill the furnace with wood or coal.

In winter, understandably, the room started out very cold first thing in the morning.

“When we would arrive in the morning, if the fire didn’t work at first we would wear our outside gear inside and move our desks close to the furnace and then back up as it got warmer,” says Claudette. “Sometimes the school was so cold that the ink froze in the inkwells. We would put them close to the furnace and wait until they thawed before we could use the fountain pens.”

Then, later in the day, the students sometimes helped clean out the furnace.

“In the winter, we would empty the ashes in the yard somewhere,” Claudette adds. “But in the summer, we had to be more careful. If there was dry grass, we had to watch not to start a grass fire.”

Because the schoolhouses had no running water, they usually came equipped with a water pail and a dipper for all the children to use. One family would bring water in the morning, and then a student would act as caretaker and sweep the floor at the end of the day. It wasn’t uncommon for all students to have to tidy up the classroom in the afternoon before anyone was allowed to leave.

Most one-room schools also had an outhouse, a flagpole, and a barn or shed to house the horses used for transportation. The outhouse toilet paper most often consisted of old Eaton’s catalogue pages, or the green wrappers used to cover Christmas oranges.

“I went to a one-room schoolhouse with 42 kids, eight grades, and one teacher,” says Marilyn, a student who attended Plankey Plains School in southern Manitoba. “There was a small barn in the back for horses.”

However, Marilyn’s main memory of school has more to do with an embarrassing academic struggle.

“I remember I got a mistake on our weekly spelling test and had to write it 500 times. ‘Burnt’ was the word I got wrong. I still remember it!”

The schoolyards usually had baseball diamonds or grass fields and the children entertained themselves with balls or tires. There was limited sports equipment, and games usually needed to include all age groups. Skipping ropes, jacks, and cards were common recreation items.

Gophers often made holes in schoolyards, so students would try to catch them, with the teachers taking the animals’ tails to the local government office afterward. Those government officials paid out one cent per gopher tail!

In the early days, one-room schoolhouses were used for more than just education. They were also the social centres of their respective communities since they would host concerts, dances, picnics, and in some instances church services.

According to an article published by the Manitoba Historical Society, “When rural folk were asked where they lived, many would respond with the name of their school district, because it was the only geographic label with which they were familiar.”6

Getting to and from School

Manitoba’s rural landscape is vast, and the population sparse—and much sparser 70 years ago than it is today. This meant that there had to be a school within a few miles of most families.

In those days, prior to bussing being introduced during the 1950s, children were mostly expected to get themselves to school.

The most common modes of transportation included walking or horse-and-buggy. If you got there by horse-and-buggy, the horse would be kept either in the backyard of the schoolhouse or in the adjacent barn or shed. Students then had to go check on their horses during recesses and lunch hours.

In the winter, a buggy had to be replaced with a sleigh, or “cutter.” Because it was so cold, students had to wrap blankets around themselves to keep warm. It wasn’t unusual for children as young as six to drive a few miles each way, and parents never really knew for sure whether their children had made it safely to school until they got home at the end of the day.

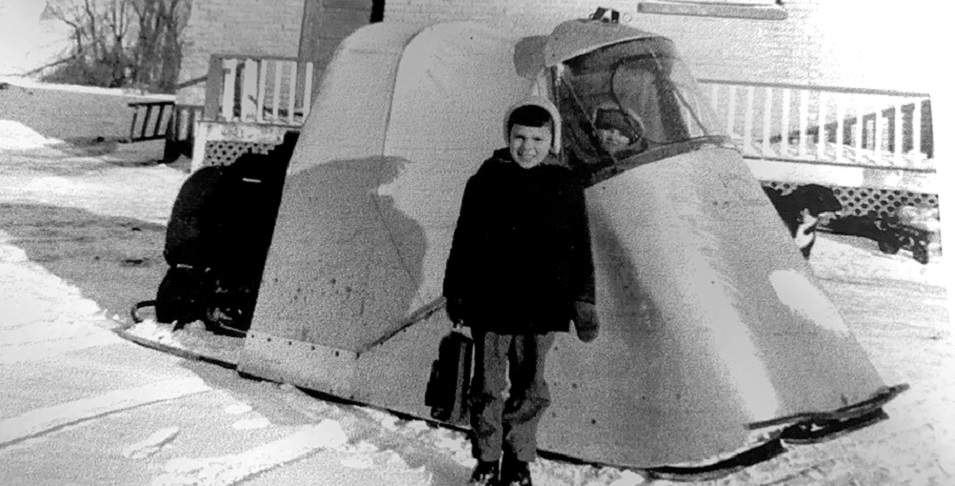

Some students were lucky enough to have a neighbour who would drive them to school with a snowmobile and tarp covering. Other families built their own covered trailers large enough to pile in all the neighbourhood kids.

“In the winter, Dad would drive his snow machine and pull us in a sled along with other kids from the neighbourhood,” says Lorraine. “We would drive anglophone kids and we all became friends even though I didn’t speak much English when I started school. I got more comfortable with them and broke down the language barrier.”

Attendance was never one hundred percent, since there were so many transportation barriers, such as snowstorms, flooding, and crossing rivers and streams during spring thaw and winter freeze-up.

“When we walked to school in the springtime, there were lots of iced-up ditches,” Susan recalls. “We would run across the ditch and slide and hopefully not break through. If we did, we would get to school and put some of our clothes near the woodstove to dry them out.”

“We used to have to cross the Red River to get to school,” says another student. “We would use a boat and then in the springtime we would sometimes jump from ice float to ice float to get across.”

Martha recalls having to walk one and a half miles to get to school.

“One day, on our way home from school, the road had gotten washed away earlier after a big storm,” Martha says. “When we got to the washed-out part of the road, we were contemplating how to cross it when a man from down the road happened to show up with his team of horses. He got down from his cart. He had big rubber boots and crossed the washed-out part of the road and carried all of us kids, one under each arm, across.”

And of course another transportation barrier was vehicle breakdown. Nowadays, it comes in the form of flat tires. Back then, the same sort of problem took on a new dimension.

“One time, we were taking the horse-and-buggy to school and the wheel fell off,” another student says. “Luckily we weren’t too far away from a neighbouring farm and the man helped us fix it. We were late for school that day and got a talking to… even though it wasn’t our fault.”

Religious and cultural holidays also affected attendance for those of immigrant backgrounds, and in the spring and fall many children had to stay home from school to help out on the family farm either with labour or assisting with childcare of younger siblings.

Kids also missed school often in the winter due to influenza, and they weren’t allowed to go to school if they lacked the proper footwear.7